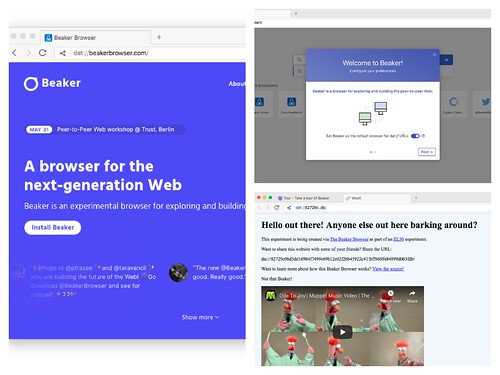

Beaker is a new peer-to-peer browser for a Web where users control their data and websites are hosted locally. An early prototype of Beaker Browser. Beaker Browser is built on Chromium using the Hypercore Protocol that a few other small peer-to-peer projects are based on. BitTorrent is a good example of a popular peer-to-peer application/protocol, and that is how this browser works as well. In the above example, BeaKer runs as part of AC-Hunter. When you perform the install, you get an additional set of services (ElasticSearch and Kibana are loaded onto either the AC-Hunter server or a separate machine if load requires). These accept network connection information from your Windows systems provided by an agent that.

Web site: beakerbrowser.comCategory:Network

Subcategory:Web Browsers

Platform:Linux, OS X, Windows

License:MIT

Interface:GUI

Programing language:

First release: August 1, 2017

Beaker Browser – an experimental peer-to-peer Web browser. It adds new APIs for building hostless applications while remaining compatible with the rest of the Web. It is an open-source application in development by Blue Link Labs.

Features:

– Deploy instantly – Create a new Hyperdrive site with one click.

– Co-host sites – Reduce costs and help keep sites online using peer-to-peer hosting.

– Build p2p apps – New Web APIs make building peer-to-peer apps easier than ever.

– Explore files – Hyperdrive is a fully-featured filesystem which you can explore.

– Run commands – Browse the Web and get work done with the integrated terminal.

– Edit source – The integrated editor lets you work side-by-side with your page.

If humans do not have free will–the ability to choose–then actions are morally and religiously insignificant: a murderer who kills because she is compelled to do so would be no different than a righteous person who gives charity because she is compelled to do so.

Jewish tradition assumes that our actions are significant. According to the Bible, the Jews were given the Torah and commanded to follow its precepts, with reward and retribution to be meted out accordingly. For Judaism to make sense, then, humans must have free will.

The Free Will Problem

There are theological problems with the idea of human free will. Jewish tradition depicts God as intricately involved in the unfolding of history. The Bible has examples of God announcing predetermined events and interfering with individual choices. Rabbinic literature and medieval philosophy further develop the notion of divine providence: God watches over, guides, and intervenes in human affairs. How can this be reconciled with human free will?

There is also a philosophical problem, which derives from the conception of God as omnipotent and omniscient: If God is all-powerful and all-knowing, then God must know what we will do before we do it. Doesn’t this predetermine our choices? Doesn’t this negate free will?

Modern science has raised yet another problem. Some contemporary scientific thinking and research attributes much of human behavior to biological and psychological factors. If these factors in large part, determine our behavior, how can we be held responsible for our actions?

Responding to the Free Will Problem

Biblical and rabbinic literature don’t systematically analyze philosophical issues, including the concept of free will. The Bible is clear that God has a role in determining human affairs, and equally clear that, in most cases, human beings have the ability to choose between right and wrong. This contradiction does not seem to bother the biblical writer(s), and thus the Bible provides no clear solution to the free will problem. Some rabbinic sources indicate an awareness that divine providence and human choice might be contradictory, but no systematic solutions are articulated.

Solving the free will problem–especially the problem of divine foreknowledge–was a major aspect of medieval Jewish philosophy, which offered an array of possible theories about what God knows and doesn’t know. For example, Gersonides suggested that God knows the choices from which we will choose, but doesn’t know the specific choice we will make.

Gersonides’ position–seemingly radical because of the limitations it puts on God’s capabilities–pales in comparison to the unique position of the Hasidic leader known as the Izbicer Rebbe. He claimed that there is no philosophical problem related to freewill, because humans don’t have free will. While humans have control over their thoughts and intentions, God is the active cause of every human action. This sort of determinism is often referred to as “soft determinism.” “Hard determinism” refers to the idea that even thoughts, intentions, and feelings are predetermined.

Modern Jewish thinkers also address the problem of free will, though more often than not, instead of solving the problem of how it can exist, they discuss when and where it does exist.

In many ways, free will in the modern period is an even more significant philosophical issue, as contemporary life emphasizes personal autonomy in a way that traditional societies didn’t.

Beaker Browser Ios

Join Our Newsletter